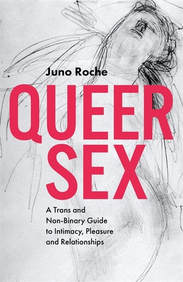

I recently read a post about recommended new releases for feminists. On that list was Queer Sex: A Trans and Non-Binary Guide to Intimacy, Pleasure and Relationships by Juno Roche. The blurb for the book sounded great, and the recommendation was incredibly enthusiastic. Although I’m a heterosexual cisgender woman and ally, I want to learn more about experiences outside of my own around sexuality and gender so I located an advance copy of the book.

I quickly discovered I was not really part of the target audience for Queer Sex. Roche wrote this book as a way of working through her own issues around sex after having had bottom surgery in the UK. She was struggling with dating and what sex and relationships “should” be for her, so she turned to journaling and interviewing others. Those journal entries and interviews are then compiled into an awkward volume. Roche hoped that her book would serve to help others also struggling with the same issues. This is an incredibly important goal, and one that obviously needs far more exploration.

However, the result is that there is often not enough basic education for readers like me who came to the book with very little knowledge about the process of transitioning or the intricacies of surgery. For example, Roche begins talking about dilation after her surgery. To me, gynecological dilation is the cervix opening for a baby to be born. Obviously, that wasn’t what she was talking about, so I had to go do some research. Likewise, Roche interviews someone who talks about chemsex. Roche herself says she doesn’t know the terms involved with chemsex, but I didn’t even know what chemsex is. These are the types of concepts that a well-written and well-edited guide book would have made clear through a few sentences or a footnote.

Queer Sex clearly demonstrates that there is a huge gap in the NHS in the UK for helping individuals dealing with issues around their gender and sexuality. Unfortunately, Roche doesn’t explain how the process of gender surgery happens in the UK, so those of us who live elsewhere (including me in the US) can be confused by what she discusses. To me as an outsider, it seems truly unethical that the system would provide her with the changes to align her body with her identity but then not help support her in the emotional transitions and experiences that happen as well. Of course, I realize things are probably not much better for those in the US, but it left me wondering why this gap in support exists and how it could be fixed.

Roche clearly struggles with low self-esteem, and this comes through very clearly in her writing. While there is a time and place for exploring low self-esteem, a “guide” to queer sex doesn’t seem to be the appropriate place for it. Roche’s lead-in to the first interview is self-disparaging, and while she means it to be humorous, the result is actually painful to read as Roche’s account of herself comes across as self-loathing. So often throughout the book I just wanted to hug Roche and tell her to believe in herself, something she clearly struggles to do. To me, it felt as though Roche really needed to be working intensely with a sex therapist rather than writing a book. Her journaling from this time could easily be edited and integrated and included in a future work once she was grounded enough in herself to write a coherent narrative.

Amid all the missing information and poorly integrated personal emotion is some very important and very fascinating content that should have been the focus of the book. During the transcribed interviews in the book, Roche and her interviewees explore what it means to be trans and/or non-binary. These people are trying to understand their own bodies, both pre- and post-op, their sex drives, their attractions, and their orgasms. They discuss generational differences between transwomen and what’s expected of transwomen, how trans people define themselves, and how others define them. The book explores whether genital surgery is normative and whether or not being trans is still defined by a binary system (which most agree it is). They ask questions such as “Do you have to have female genitals to be a transwoman?” These issues are the heart of the book, but because they are only discussed in the transcribed interviews, they are not fully explored.

Overall, Queer Sex reads like the combination of a journal and series of interviews that hasn’t been well-integrated or well-edited into a unified work. The text is repetitious in places and very self-indulgent in others. Roche’s vulnerability and exploring her experience is wonderful, but her writing needed to be edited for coherence. Her prose is absolutely gorgeous at times, such as when she discusses interviewing Kuchenga who “has a strange little triangular house, with triangular rooms, on the edge of the roundabout. As I enter her domain, I feel instantly like we are in a story full of content. And as soon as she starts to unfurl her works, I remain almost spellbound for the next two hours or so. Unfurl her words she does with a kind of languid confidence that is sonically beautiful.” However, her writing isn’t able to shine because of the poor organization and editing. Queer Sex really feels like it was only half-done and rushed to press rather than taking the time to make it into the stellar book it could have been.

Queer Sex contains some very important content about issues that we all should be discussing. We are all sexual (or asexual) beings, and our society’s views on sexuality and gender are changing rapidly. Even as a heterosexual cisgender woman, I recognized issues that I personally have struggled with in the dating world that Roche touches upon. I hope in her future works, Roche spends more time integrating, exploring, and editing these important topics.

©2018 Elizabeth Galen, Ph.D., GreenHeartGuidance.com

RSS Feed

RSS Feed